What stories does it hide inside its walls? Who were its conquerors and who were the prisoners serving their sentences in its dungeons? Why did this location attract the settlers since ancient times? Take a walk through the turbulent history of the Petrovaradin Fortress.

In the Olden Days

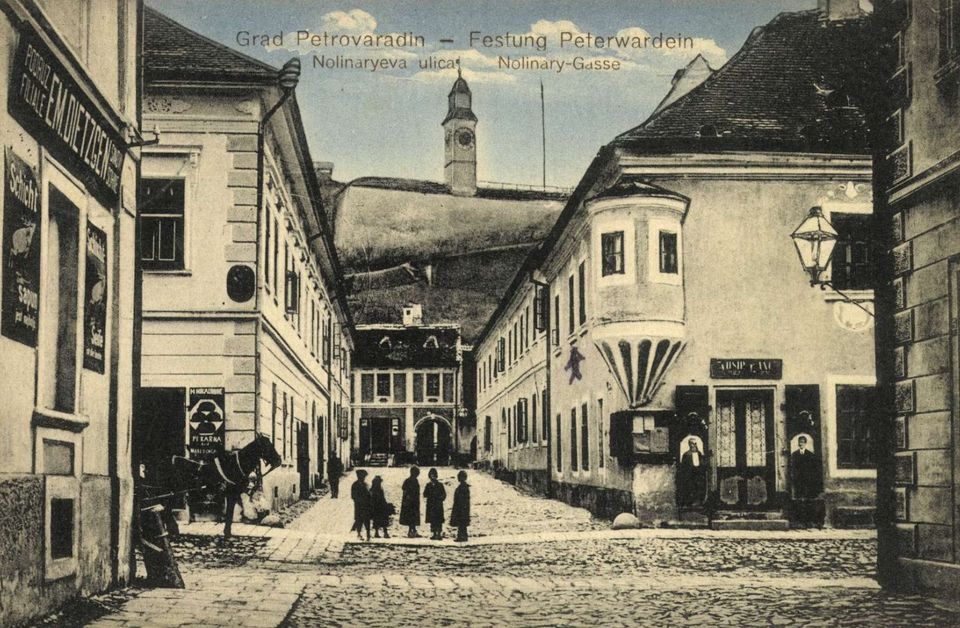

The dominant position of the Petrovaradin rock emerging from Fruška Gora has attracted people for more than six millenniums. Thus, the oldest remains date back to the Neolithic period (around 4500 years BC). At the beginning of the first century BC, this area was populated by the Celts, and then, two centuries later, by the Romans, who built the fortification ‘Kusum’ between today’s Petrovaradin and Sremska Kamenica. In that time, on the Petrovaradin rock, there was a lookout intended for the Roman border called Limes, which resisted many attacks. With well-organised signalisation, a short message from these areas would quickly arrive in Rome, in only around one hour and 30 minutes. In the fifth century, these areas were destroyed by the Huns. With the fall of the Western Roman Empire in 476, the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) ‘anchored’ its borders, while at the site of the Kusum, they built their fortification called Petrikon.Medieval Hungarian Rule

The turning point in the history of Petrovaradin was the year 1235 when the king of Hungary Béla IV settled the Cistercians from the province Champagne in France. In that time, the first big military fortress within the parish of the Cistercian monastery was built in order to ensure protection from the Mongols. Petrovaradin started to become more and more important, while the historical sources of that time call Petrovaradin ‘Varoš Varad.’ Petrovaradin was first mentioned in 1521 by the Hungarian writer and prelate Antun Vrančić, under the name Stari Petrovaradin (eng. Old Petrovaradin). In the middle ages, here lied the Cistercian abbey and the monastery of Blessed Mother. The abbey was famous for its Srem wine from Petrovaradin, which became a brand. Before the Battle of Mohács, the former rich monastery vanished, while Srem wine was transferred in the Hungarian town Tokaj.Suleiman the Magnificent

Under the leadership of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Turks conquered Petrovaradin on 27 July 1526. The famous Turkish travelogue writer Evlija Čelebija called Petrovaradin ‘a key to the city of Buda,’ emphasising the strategic position of the fortress on the Petrovaradin rock. The Turkish reign will last for 161 years, keeping the fortress in its medieval form, with certain adaptations and upgrades.

The Period of the Habsburg Reign

The Austrian army occupied these territories in 1687 and urgently started with the preparations for building a new defence object since there was still a long battle to fight ahead of them, a battle for the Danube region in the Balkans. The Turks gained back Petrovaradin only for a short while in 1690. After the defeat near Slankamen, on 17 August 1691, they lost all their occupying territories throughout the whole Srem. After that, there was a long period of no wars, which will allow for the systematic construction of a new fortress.

Building Today’s Petrovaradin Fortress

The destruction of medieval and Turkish settlements in 1692 laid the foundations of today’s Petrovaradin Fortress. The project was the idea of a French architect, Marquis de Vauban, who was one of the leading engineers of the modern fortresses in Europe during the 17th and 18th century. However, Vauban never got to see this fortress. According to some unconfirmed sources, the conceptual architectural design was stolen with the help of those days’ espionage, while the Austrian experts adapted and modified it. The base of the colossal construction had several stressed parts – Upper Fortress, Lower Fortress in the North, i.e. Wasserstadt, Hornwerk in the South, Small Fortress on the island, i.e. Inselšanac, and Bridgehead – Brukšanac.

With certain interruptions, the construction came to an end in 1780, with an urban suburbium built as well. Serbian people worked on building the fortress as well. Serbs cursed the fortress, due to the difficult work they had to do, saying they wish the ‘sour wood’ would ruin its foundation and knock it down. They say bricks were passed hand by hand, starting at the brickyard at the trenches (Trandžament) all the way to the construction works.

Over a long period of time, the fortress was designed by the Austrian military engineers Count Mathias Keyserfeld and Count Luigi Ferdinando Marsigli. The colonel Michael Wamberg was in charge of the work itself, and after him, the one in charge was the colonel Gisenbir. Nowadays, the tombstone with an engraved epitaph to the Colonel Wamberg is being kept in the Military Hospital – the former Franciscans monastery in the water town of the Petrovaradin Fortress. The construction works were supervised by Franz Joseph, Prince Eugene of Savoy, count Karafa and the field marshal Kaprara. The hundred years’ construction of the fortress lasted in the time of the Austrian emperors Leopold I, Joseph I, Charles VI, Maria Theresa and Joseph II.

In the period from 1764 until 1776, the military engineer major Schroeder was in charge of the construction of the countermine system (the underground military gallery) underneath Hornwerk (South of the established Petrovaradin). Between 1768 and 1776, the four-story underground was built. The total length of the underground chambers is presumably 16 kilometres. It’s possible that the real length is much larger than that, since, when you visit the underground, you get a feeling that part of it was built outside the documented frames. This unique system had the planned installations of the minefields, as well as rooms for accommodating the army and storing the weapons, all this in order to defend the fortress. It was estimated that the underground military galleries could accommodate around 30 thousand people in emergency situations. Within the underground, two additional war wells were built – the bigger one at Topovnjača, while the smaller one, the well of the Joseph II, was built in the deep underground of Hornwerk. The larger well, which was mistakenly called Roman, is 4 meters in diameter and 60 metres deep, and the smaller one, later popularly called Kaiser, is 2 meters in diameter and 39 metres deep.

The year 1780 is mentioned as the year the Petrovaradin Fortress was built, although some works lasted a couple more years. It became the most contemporary armed fortress in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy. It spreads on 112 hectares and has a ‘water town’, i.e. small channels between the ramparts that are filled with water from the Danube when needed. It also spreads across the Upper Fortress, which represents the tourist attraction nowadays. This fortification is the second largest in Europe. The only bigger than this is the fortification in Verdun, but it suffered a great deal of damage during the First World War. The colossal fortification with its army was impossible to take over and so people called it ‘Gibraltar on the Danube.’ In the time of the Napoleonic Wars, the valuables from the Vienna treasury were kept in the fortress.

The fortress was connected with the Bridgehead on the left bank of the Danube by building the pontoon bridge (1697 – 1698). There, a town with several hundred citizens started to develop. They first called it Petrovaradinski Šanac. After the Treaty of Karlowitz was signed in 1699, the number of citizens started to grow and it became one of the main border towns between Austria and Turkey.

The last phase of building objects within the fortress complex started in the middle of the 18th century. Within the Upper Fortress, the main buildings were built, namely, the Long Barracks, Simple Barracks, Gunboat, which was later named Mamula’s Barracks. The famous gates of the fortress are the Belgrade Gate, Molinari’s Gate, Dvorska (The Castle Gate), Leopold’s Gate, the Gate of Charles VI and the Gates to the Šanac and the Rampart. The plumbing system was also built.

The Clock Tower

The tower with a large clock is situated at the St. Louis’ bastion at the Petrovaradin Fortress. The clock originated in Alsace, France. Maria Theresa gave it to the citizens of Novi Sad as a present at the beginning of the 18th century. Today, the clock still works and it functions the same way it did in the past. It is being wounded manually every day. An old citizen of Novi Sad, Lajoš Lukači, has been winding the clock for years. He got the February Award of Novi Sad for his voluntary work. The interesting fact about this clock is that the big hand on the clock shows hours, while the small hand shows minutes so that the boatmen can see what time it is. During that time, you had to pay in order to use the clock. Except for showing the time, the clock had other purposes as well. Namely, in addition to the clock, there was a mechanism that was used for navigation, but it no longer exists. The boatmen could see whether the river was passable by following the signalling. Thus, the fortress itself played an important role in controlling the Danube navigation. At the very top of the tower is a pointer showing the sides of the world. There is also a weather vane above which is a symbol of a heart, instead of a spear (which is often situated on fortifications similar to this one). Another interesting fact that has to do with this clock lies in its punctuality. When it’s cold, the clock is a few minutes late, while when it’s warm, the clock is a few minutes ahead. This probably has something to do with its mechanism. Due to this, the clock was named ‘The drunk clock.’

The Fortress During the 1848 Revolution

The most tragic day in the history of the Petrovaradin Fortress and Novi Sad was certainly 12 June 1849, when the Hungarian revolutionary army, by order of the general Pavle Kiš, bombarded Novi Sad with 200 cannons. The garrison on the fortress betrayed the emperor and cojoined the national forces of Lajoš Košut, who asked from Vienna the independent state of Hungary. The dreadful bombarding left Novi Sad almost completely razed to the ground, while the citizens were on the run, looking for rescue. A longer period of peace came after the collapse of the separatist forces of Lajoš Košut, who emigrated in 1849.

The Clatter of the Prison Chains

When the fortress was finally built, the circumstances changed, especially with the Austro-Hungarian agreement in 1867 and the weakening of the Turkish empire. The military-strategic importance of Serbia decreased. Petrovaradin then became an administrative-military and espionage-intelligence centre with a military command, and the fortress became an outpost of the Austrian Empire towards the Balkans. The Petrovaradin Fortress became more and more of a dungeon. ‘Day and night, the clatter of the prison chains was heard from the underground,’ wrote Mihajlo Polit Desančić.

Some of the most famous prisoners of the fortress were the French philosopher René Descartes, who stayed here for a short period of time; Đorđe Petrović Karađorđe, who was interned after the First Serbian Uprising and before leaving for Russia; the legendary Hungarian runaway Roža Šandor; the Serbian socialist Vasa Pelagić; the champion of the Serbian Youth Movement Vladimir Jovanović, who was accused to had participated in the Conspiracy which lead to the murder of Mihailo Obrenović; the Bulgarian literary man Ljuven Karavelov, the opposer of the reign of the Prince Mihailo Obrenović; the Serbian politician and journalist Jaša Tomić, who was arrested for having killed Miša Dimitrijević and later for ‘press violation’; the Croatian poet Antun Gustav Matoš, who was arrested for desertion; the Yugoslav writer and Nobel laureate Ivo Andrić, as a member of Young Bosnia; Josip Broz Tito, as a young Austrian sergeant, was imprisoned for a minor offense, and later, as a statesman, he brought the leaders of the Non-Aligned Movement here.

The Fortress Today

In the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between the two world wars, there were two barracks at the fortress – the Air Force School and the command of the War River Flotilla. Up until 1948, the Petrovaradin Fortress served solely as a military facility. In 1951, it was placed under state protection and has been a cultural and tourist object ever since. The museum and the Archive of Novi Sad, the hotel and the restaurants, the ateliers and fine art galleries, the Academy of Arts, the Astronomy Observatory with Planetarium and other objects, reside at the fortress. The famous music festival ‘Exit’ is held here. So far, all big destructions bypassed the Petrovaradin Fortress; thus, the fortress is said to be one of the most preserved and most beautiful fortifications in Europe.

Autor: Author: Ljiljana Dragosavljević Savin, master historian

Foto: Jelena Ivanović, Old Photographs of Novi Sad Facebook page (with the administrator permission)