The exhibition ’The Darkest Wave,’ part of the Kaleidoscope of Culture finale, will run in the District until 19 October. It offers a combination of artistic exploration and a fresh perspective on one of the most provocative eras in Yugoslav cinema. Through new media art, the exhibition not only sheds light on the visual aesthetics of the Black Wave but on the political and social frameworks within which directors like Aleksandar Petrović, Dušan Makavejev, Karpo Godina, and Želimir Žilnik created their films. The work of Monika Bilbija Ponjavić, PhD, allows audiences to experience how these rebellious filmmakers challenged the norms of their time, creating works that still resonate today. In an interview for Visit District, we discussed the challenges and inspiration for the exhibition, as well as the continued impact of the Black Wave on art and society.

The Black Wave is described as a rebellious and provocative movement in Yugoslav cinema. How does ’The Darkest Wave’ reinterpret this aesthetic through contemporary artistic installations? How do you perceive the artistic and political context in which these directors worked?

When the idea of the exhibition was proposed, the decision before me was relatively simple. I had to choose whether to create a traditional archival and documentary exhibition about the so-called Black Wave or not. The answer was, of course, no.

I say ’of course’ because, for me, there was no doubt. While archival and documentary exhibitions are great in some cases, they are not my style. Not only do I not feel comfortable working that way, but I am primarily focused on storytelling through scenographic means. Space and text have always been my main forms of expression since I am, first and foremost, an architect and scenographer, and only then a visual artist and art theorist.

I decided that the exhibition would be about the giants of Serbian and Yugoslav cinema, often labeled as part of the Black Wave (even though they never fully belonged to it). In other words, we’re talking about Aleksandar Petrović, Dušan Makavejev, Živojin Pavlović, Želimir Žilnik, and Karpo Godina. I also included Lazar Stojanović, whose student film became a ’weapon’ in the fight against so-called ’negative phenomena’ in Yugoslav culture. Even though Stojanović’s work technically does not belong to this era, it was used to attack these great filmmakers.

Once I knew the story I wished to tell, the next step was to shape the space. I reconfigured the spaces, designing them to suit the narrative. The goal was to create three autonomous, interconnected sections. Petrović, Makavejev, Pavlović, Žilnik, and Godina are housed in the Radionica, Stojanović in Biro, and the historical context in Menza. Each of these spaces has its own distinct visual language, marked by symbolism. For example, the ’big five’ filmmakers are represented through a series of oversized screens accompanied by similar but subtly different sounds. Stojanović’s work is presented through fragmented ’monoliths’ that are not easily accessible. Meanwhile, the historical context unfolds in complete silence under the watchful gaze of Josip Broz Tito. Keywords like verticality, monumentality, and sacredness define the essence of the exhibition.

Given your background in scenography, was this approach a natural outcome? Did Novi Sad’s status as a UNESCO Creative City of Media Arts influence the decision to explore this topic?

Yes, it was both logical and inevitable. Novi Sad, cinema, and I are intertwined in a perpetual bond. Not doing a new media exhibition in a city recognized as a UNESCO Creative City would have been a missed opportunity—especially given the fact that the Yugoslav auteur film movement was ahead of its time. In fact, I believe it still is.

In my academic work, I often focused on transforming public spaces for film festivals and screenings, curating films in museum settings, and creating scenographic works tied to identity. This exhibition brought everything together—what, where, how, who, and why—into one cohesive project.

For me, making an exhibition about film that is less alive than film itself was not an option.

Why is the exhibition called ’The Darkest Wave’? Does it refer to the most controversial filmmakers or the most censored films of that period?

Yes, it does. The title, which I didn’t come up with, is perfect—brilliant, even. I wish I had thought of it. It captures the essence of the exhibition and reflects my own perspective on Vladimir Jovičić’s text, which coined the term ’Black Wave’ as a pejorative. In that sense, ’The Darkest Wave’ is an ironic take on the Black Wave, which was already a derogatory label for Yugoslav auteur cinema. The darkest. The best.

How do the spatial video installations in Radionica, Menza, and Biro spaces deepen the understanding of the artistic and social value of the Black Wave?

The idea was to tell a personal, poetic story about these directors through their films. I used their cinematic language and narrative structures to build the installations.

For example, Karpo Godina’s film On Love Skills portrays a group of soldiers and young women living side by side but never interacting. Drawing from this, I created an installation called On the Sentimental History of the Yugoslav People’s Army, confronting their exaggerated portraits for the ’first time,’ allowing them to make direct contact. Each installation follows this pattern—extracting the essence of a film and translating it into spatial form while maintaining the spirit of its creator. The title itself is multilayered and also conveys meaning, in addition to being a small homage to Pekić.

I processed each film individually using the same approach and transformed it into a spatial video installation while preserving its essence. In practice, this means that I extracted the core (text) from each work, reshaped it, and presented it in the language of its director. I then embodied that essence using theatrical tools in relation to the space. For example, Karpo is all about portraits, Makavejev emphasizes editing (so-called Serbian Cutting), while Petrović is static yet full of life. Both I Even Met Happy Gypsies and the video work and animation Nedogled II, my self-portrait, are large images, rich in details, motifs, and symbolism… both allowing you to capture the moment of Bekim’s ’ascent and downfall.’

The filmmakers of the Black Wave often challenged political authorities and social norms. Which messages from their films remain relevant today?

Their works show that evil is ever-present, rooted in ignorance and fear. That hasn’t changed to this day. Their films remind us that freedom is the only thing worth sacrificing for, and that courage—facing evil—is the highest virtue and responsibility of a thinking person. Don’t let the light within you turn into darkness.

The programme of ’The Darkest Wave’ also included a discussion with Želimir Žilnik, a key figure of the Black Wave. How was your collaboration with him?

Želimir Žilnik is one of my favorite Serbian directors, and his film Early Works is very close to my heart. I was nervous about the responsibility of interpreting his work, but both he and his wife Sarita Matijević Žilnik were incredibly kind and supportive throughout the process.

Were there any unexpected discoveries during your research?

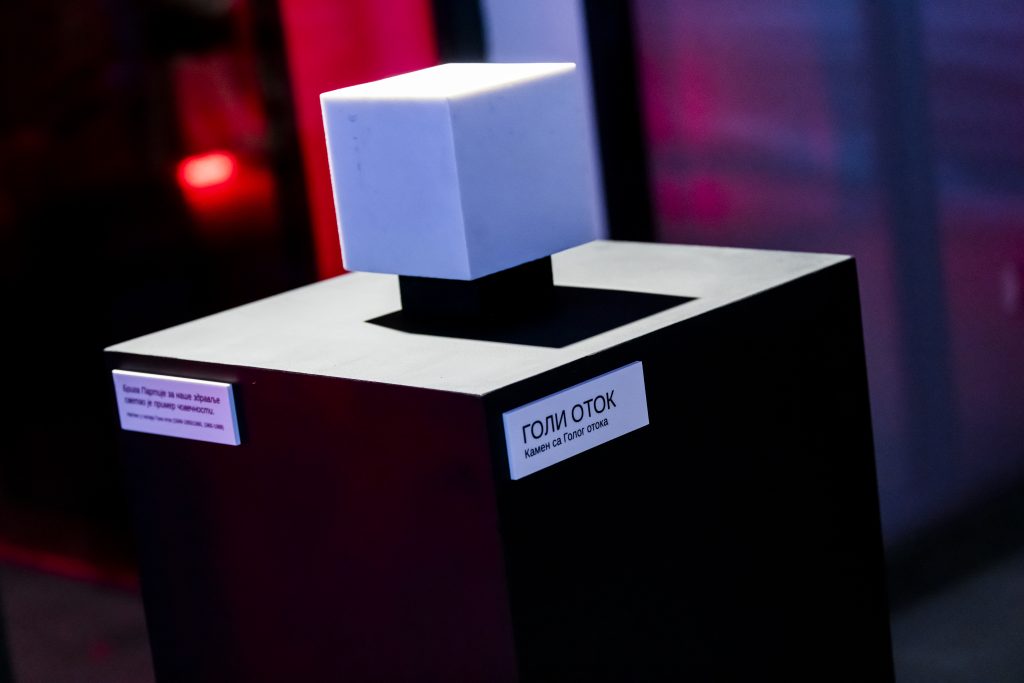

Yes, I learned that Miroslav Krleža was involved in establishing the Goli Otok prison camp. That information was shocking.

The exhibition combines artistic interpretation with archival documents. How did you choose the materials, and how important is artistic freedom in presenting this period?

Aside from what I already knew about this period, the research lasted nearly a year. In the end, I ended up with a pile of material that I had to systematically organize and largely discard. I kept only what was functionally significant to me, as my goal was to convey the maximum number of information in the shortest format possible, but in such a way that it only introduces you to the story of these twelve years. ’The Darkest Wave’ is, as I see it, a prologue to the exploration of Yugoslav new auteur cinema and everything that happened around it during that time. About its mystification and demystification. How good this prologue is depends on how far you will dive down the rabbit hole. Either it has intrigued you or it hasn’t. And the rabbit hole is seriously deep.

Therefore, everything you see at the exhibition served the story. That’s how I chose. Now, when I look back, I wouldn’t add or subtract anything. That’s it. And I had absolute freedom in that… to choose, to think, to decide… to say what I want, how I want, and how much I want. That’s exactly what I did. And for that, I am also seriously grateful. For the freedom to do it at my own pace, in my own poetics and sensibility, according to my vision of how that exhibition and that space should look. And to stand behind what has been done. If you can’t stand behind your decision, your stance, behind what you have publicly said and done—since every art, when it comes before the audience, becomes a public speech, a public matter—if you don’t have a stance, then that’s not it. It’s not freedom. Then it’s a compromise and bending your spine. To gain that kind of trust to do something without bending your spine, at all instances, that is freedom. And I think the entire team that participated in the process of creating the exhibition felt that key four days where cruical for the exhibition to happen or not. Zoran, Zvonko, Boris, Nemanja, Dušan, Ivan, Marko, Miloš, Nemanja, Minja, Nikola, Strahinja, Dragomir, Anđelko… We all breathed as one, trusting each other, believing in what we were doing, wanting it to succeed, which in these spaces and conditions was not an easy task at all. On the contrary. But we succeeded. That breathing—there is no better feeling than that.

How is the Black Wave positioned in contemporary art, and can this retrospective inspire new interpretations or debates about artistic freedom?

The beauty of these films lies in the timelessness of their topics—freedom, life, death, belonging, speech, responsibility, good and evil, morality, and free will. These topics remain relevant today. The cinematic language of the Black Wave was groundbreaking, and it continues to inspire filmmakers and audiences alike. Art and freedom are synonymous—one cannot exist without the other.

What has been the audience’s reaction?

I am satisfied. I have achieved what is always my goal when I exhibit. In the process of creation, I am a mathematician. Everything must be in a specific place for a specific reason and with meaning that only I understand. In my mind. Which I see so clearly, but which I absolutely cannot verbalize, explain, or convey to others. I only ask to be trusted. That is my architectural mind.

However, in the output, in the final product, reason plays no role; reason no longer exists, because in the output, only emotion matters. The audience’s emotion. That is always my goal, to create a space where you feel something. That is the artist in me.

And I believe that, at exhibitions like these, which demand time, the act of being present in the space is very important. If you can afford it, go alone and stay. Lie on the floor, sit in front of the screen—whatever feels right… just stay. It heals.

There is this one reaction I heard at the opening that stuck with me: ‘I don’t know what I feel, but I feel it intensely.’ That is exactly what I strive for. In that moment, I knew I had succeeded. Because if you manage to touch one person with your inner world and evoke something in them, that’s it; you have succeeded. For me, it has always been enough to reach just one person. Always.

Monika Bilbija Ponjavić, PhD, is an architect, scenographer, visual artist, and art theorist. Her work focuses on transforming spaces through scenographic means and creating video, audio, and light installations. She holds degrees from universities in Banja Luka, Amsterdam, and Belgrade, with a PhD from the University of Novi Sad.

Author: Marina Marić

Photo: Srđan Doroški, Vladimir Veličković