Relocations or migrations have been present since ancient times and are inextricably linked to human history. The city of Novi Sad and Vojvodina in general, throughout their history, have been an area of great relocations or migrations, and today they are known for their multiculturalism. All these movements were conditioned by historical circumstances and whirlwinds of the war. People who went through migrations brought their culture, language, religion, tradition, and habits of their old region to this area, mixing them with the existing ones, but they also passed on their destinies, experiences, and life beliefs. Different ethnic communities have created an unusual potential for the turbulent and successful development of Novi Sad.

Thanks to the cultural needs, all these ethnic communities created spiritual and material goods, which ended up representing the cultural identity, the corpus of Novi Sad. Migrations have resulted in the fact that today Vojvodina has a population of less than two million and 26 national minorities, with six languages having official status – Serbian, Hungarian, Croatian, Slovak, Romanian and Ruthenian.

The First Settlements Date Back to the Palaeolithic Era

Traces of the oldest human settlements in Vojvodina originate from the Old Stone Age (Palaeolithic), while in the Late Stone Age (Neolithic) the Starčevo culture and, somewhat later, Vinča culture developed here. The area of Vojvodina was flooded with waves of migrations of Illyrian, Thracian, Sarmatian and Celtic tribes, and in the 1st century the Romans, then the Germanic Goths, Huns, Gepids, and in the 6th century with Slavs and Avars. At the beginning of the 7th century, there were also Serbs among the Slavic tribes that inhabited Pannonia and the Balkans. In the 9th century, a warrior tribe of Hungarians arrived in the Pannonian Plain.

The Influence of the Turkish Empire

From the middle of the 16th century until a century and a half later, the entire territory of Vojvodina was ruled by the Ottoman Empire. The deserted cities of Vojvodina were then inhabited by an ethnically diverse population – Serbs, Turks, Arabs, Greeks, Aromanians (Cincari), Romanians, Jews, Armenians… Most of them were merchants and craftsmen from the Turkish regions in the Balkans, who brought a strong oriental spirit with them to Vojvodina. The Turks moved a group of Catholic Bunjevci from the Dalmatian Hinterland to today’s Bačka, and the Šokci from Bosnia were relocated to Podunavlje. In the First Great Migration of Serbs in 1690, 37,000 Serb families (around 185,000 people at least) arrived in Vojvodina, and in 1740 the Second Great Migration of Serbs followed, during which, according to Vuk Karadžić, as many as 80,000 of the migrants were killed in Turkish attacks, which is significantly more than the number that reached Vojvodina. Serbs went on to become the largest ethnic community in Vojvodina.

The First Inhabitants of Racka varoš

In Podunavlje, on the left shore of the Danube, a settlement named Racka varoš, the Serb City, Petrovaradin suburbs, Petrovaradinski Šanac… was created. It was a swampy, often flooded, and unhealthy landscape, with harsh winters, windy springs and autumns, and hot summers, full of

mosquitoes and other insects. Such an area was not pleasant to live in, but its favourable geographical position was the decisive factor. The first inhabitants of this settlement were the builders of the bridgehead, located right next to it, and with them, Petrovaradin Fortress’ merchants and suppliers: blacksmiths, innkeepers, bakers, tailors, craftsmen who at that time went with the army and soldiers and made an income due to them. The second wave of immigrants were Bosnians and Herzegovinians, which is why the local ‘natives’ called them Sarajevans. One of the most famous is Sava Vuković from Mostar ‘who became a citizen of Novi Sad in 1776’ and who bequeathed a large sum for the founding of the Novi Sad Grammar School. The third wave of immigrants was extremely important for the progress of the city. They were citizens of Belgrade, mostly residents of the Serbian and German Danube towns and a few Greek (Aromanian) and Armenian families, who fled to the Austrian Empire after the return of the Turks (after the surrender of Belgrade to the Turkish authorities in 1739). These ‘Belgraders’, accustomed to civic life, encouraged the future struggle of the inhabitants of Šanac for independent development and gaining elibertation in 1748.

Armenians in Šanac

Among the ‘Belgraders’, Armenians also moved to Petrovaradinski Šanac. They very easily fit into the local environment in terms of communication with members of other nations, respect for state laws, and ways of life. In their private lives, they kept the memory of their family, national, and religious origins, and even the way they dressed. Economic security and enviable financial situation were provided primarily by the trade and craft activity in which they excelled. Armenians assimilated into the German community.

Greek-Aromanian Community

Migrations and the first examples of permanent settlement of Aromanians, Greeks and other Christian merchants from Turkey in the Habsburg monarchy, primarily in Hungary, began in the 17th century, and their followers began to arrive in large numbers after the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699. The Greek-Aromanian community was successfully engaged in trade and was concentrated along Dunavska and Ćurčijska streets. Their houses were typically oriental in type, with shops and craft workshops on the street side, overlooked by ćepenci, eastern shuttered windows. At the beginning of the summer, at the time when the roses were blooming, a passer-by who would walk the streets of Novi Sad could determine with certainty which houses were Aromanian. Namely, at that time, the Aromanians made slatko from roses and that is one of the Aromanian legacies of the Danube cuisine. The Greek-Aromanian community in Novi Sad formally survived until the second half of the 19th century, but they began to Serbianize their surnames long before that.

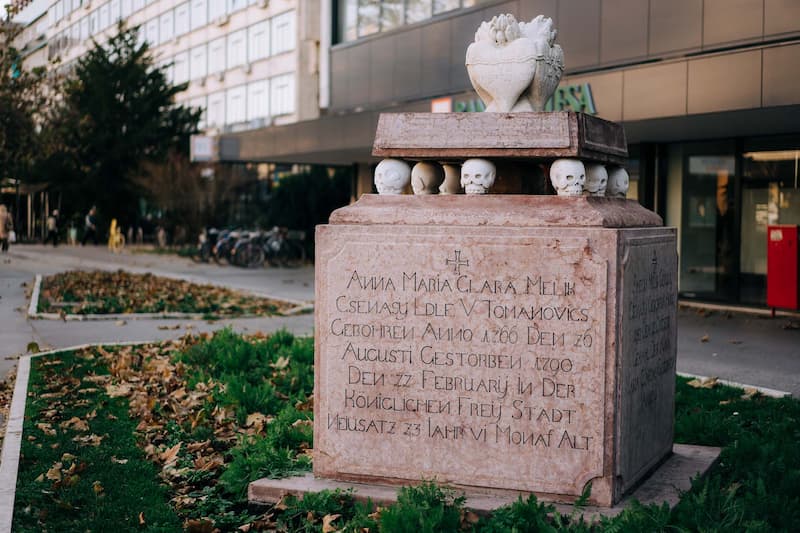

Novi Sad Jews

The first Jews in the then Petrovaradinski Šanac immigrated from the northern and western provinces of the Habsburg Monarchy, and in 1739 Jews from Belgrade moved in after the fall of the city into Turkish hands. When the Jews were given a deadline to move out of the city centre, they were assigned a place in Jevrejska Street, where the Synagogue was moved to, along with the cemetery. The Jewish community was small and kept away from all political and social events in the

city. Most of Novi Sad’s Jews died during World War II, and the majority of survivors emigrated to Israel afterwards. The cultural heritage of the Jews of Novi Sad is still very impressive.

Settlement of Other Minorities in Vojvodina and Novi Sad

After the end of the Austro-Turkish War period in 1739, the Habsburg Monarchy came into possession of fertile, but almost completely deserted territories in the area of southern Hungary. It was then decided that these territories should be inhabited and rebuilt economically. Thus began the planned immigration of Germans and Hungarians and to a lesser extent Slovaks, Romanians, Croats, Ruthenians and others. The migrations took place in three big waves: Germans from Germany immigrated to this area – in 1720, 1740 and 1760. Although they came from various parts of Germany, the local population called them Swabians (from the German region of Swabia). The immigration of Hungarians was carried out gradually and lasted for about 100 years, until the end of the 19th century. Immigrant Hungarian citizens were clerks, workers, vegetable growers and winegrowers. A large number of them settled in the part of Novi Sad Telep, where viticulture and vegetable growing have just developed. Somewhat later, the poor from Hungary, mostly Calvinists, immigrated too. Catholicism had the status of the state religion, but Protestants were granted freedom of religion later on as well, which attracted a large number of Protestant Hungarians and Slovaks. The Ruthenians arrived in Vojvodina in the 18th century (1750-1758) from the Carpathians. They inhabited several settlements in Srem and Bačka, including Novi Sad. Today, it is almost obsolete knowledge that among the immigrants in Vojvodina there were even French, Catalans and Italians. Over time, these peoples merged into Germans, Hungarians, and Serbs. Today, only traces of surnames and toponyms (Perlez) remain.

Migrations in Vojvodina Were Not One-way

Emigrations were also significant. The great changes in the population in Vojvodina were caused by the First, and especially the Second World War. After the First World War, about 14,500 Serbs moved from Hungary to Vojvodina, and larger immigration of Serbs from Lika and Northern Dalmatia was recorded. After the Second World War, there were two big waves of migration. In the first wave, about 250,000 Vojvodina Germans were expelled from Vojvodina. Thus, after two centuries, the Germans completely disappeared from this area. At the same time, colonists from Bosnia and Herzegovina and Croatia arrived in Vojvodina, and to a lesser extent from Montenegro, Macedonia, Kosovo and Metohija. The civil war of the 1990s, in the former Yugoslavia, caused new migrations. A wave of refugees (259,719 people, according to official data), Serbs from Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, flocked to Vojvodina and Novi Sad.

The citizens of Novi Sad have woven the symbolic values of their ethnic communities into the collective memory of this city, creating a special cultural identity. National cultures have become the basis of every special culture, to the extent that they confirm and express the identities of the peoples to which they belong and connect them with the cultures of Europe. In order for such a thing to be possible in one city, in the first place it was necessary to acknowledge human freedoms, lead intercultural dialogue and politics of peace, connect people and develop an awareness of common history and values. Aren’t these the very values, promoting the idea of an open democratic society, based on modern humanism, all of which Europe stands for today? Aren’t these the exact challenges that Novi Sad successfully faced, justifying the title of European Capital of Culture?

Author: Historian Ljiljana Dragosavljevic Savin, MSc.

Photo: Jelena Ivanović